For as long as humans have walked the earth, trees have been our companions. They have sheltered and sustained us, provided food of themselves and for the animals we preyed upon. It's no wonder that they have become so entwined in our imagination, and seem to reach out to all our senses; attracting us not only by their latticed beauty but also with their smell, sound and surprisingly their touch (who hasn't run their hand along the bark of a tree or marvelled over the smoothness of a Horse Chestnut)?

Trees are sometimes a source of fear, not in themselves, but by creating the dark forest that can hide our enemies. They rustle, they crack, they groan. Conversely they offer shelter and shade and life giving oxygen. They are beautiful, inspiring and practical. We hug trees, we play on trees, we destroy them, worship and adore them. We hang people from their branches, burn them for warmth, we make them into tables and whatever else we can imagine. But, despite their utility and beauty (or possibly because of it), trees remain humankind's conscience and solemn witness.

And I would like to be simple and devout, like the oak tree.

A beautiful line from Mary Oliver's book ‘Sand Dabs,’ recently tweeted by Cassidy Hall.

Naturally, trees have long appealed to artists, writers and poets as well as those working with visual medium and there are stories involving trees throughout all cultures of the world. I would highly recommend ‘The Spirit of Trees’ blog if you are interested in reading some of these, it has a great collection from around the world. I would also encourage readers to have a look at Shel Silverstein's ‘The Giving Tree', a story that while ostensibly for children, is open to a range of interpretations (the one I am most drawn to being that the tree represents nature and the boy humankind). An interesting article on the book can be found in the New Yorker.

Trees and photography

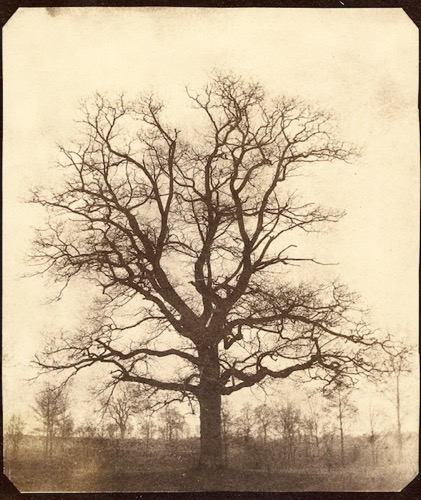

You will not be surprised to hear that trees have been a favourite subject for photographers (including this one) for as long as cameras have existed. It is fascinating to see some of the earliest photographs of trees, and to wonder how soon after the discovery of the medium mankind wanted to photograph them. Looking back, it is hard to imagine now how exciting it must have been for William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) to have assembled his tripod and heavy camera and produced, in the 1840s, his “Oak Tree in Winter”, in essence and honesty a match for the millions of tree photographs of trees which were to follow. The quality of Talbot's early calotype work is addressed in an interesting photography review by Margarett Loke:

As for his calotype portraits of trees, Talbot brought to them a sensibility akin to Eugene Atget's in his photographic record of Paris. Talbot had inherited Lacock Abbey, a country estate near Bath, and in his photographs he seems to have held as much affectionate respect for his natural surroundings as Atget did for his urban landscape.

"Oak Tree in Winter” (early 1840's) focuses on a single oak as a piece of sculpture that easily balances strength (the stalwart tree trunk) and fragility (the delicate tips of the branches). In “An Aged Red Cedar Tree in the Grounds of Mount Edgecombe,” Talbot portrays a cedar that may be getting on in years – its wide trunks furrowed, some branches broken off – but nonetheless is unbowed.

William Henry Fox Talbot. Probably 1842 - 1843, Salted paper print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

I think the challenge in photographing trees in their amazing variety is in offering them respect and authenticity regardless of whether this is in close up, at a distance, as part of compositional work, in their agony or in recording their mistreatment. Of the myriad of subjects for the photographer, the ubiquitous tree provides one of the greatest challenges for us in capturing their essence and dignity. That said, photographs such as this provide us with great examples, and I would recommend viewing Beth Moon's complete portfolio as well as looking at her book on Ancient Trees (see Further Resources below).

I will finish with a verse from E. E. Cummings, the great American poet

i thank You God for most this amazing

day:for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky; and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes

Further resources

- Ancient Trees - A portrait in time by Beth Moon - Mesmerising black-and-white photographs of the world’s most majestic ancient trees.

- Four Tips for Taking Better Photographs of Trees (Digital Photography School)

- Edward Parker's book on ‘Photographing Trees’.

- William Henry Fox Talbot's “An Aged Red Cedar Tree In The Grounds Of Mount Edgcumbe” in the National Gallery of Canada.

- Tree Photography (on-line tutorial by Gabriel Hemery).

Originally published by this author on quietsilence.net

Please email me should you have a comment or query relating to this post.

← The lonely sea and the sky | Post Archive | Dark cloud over Jubilee Tower →